I have never been particularly good at following the rules. There’s a little monster inside me that whips out its angry claws anytime someone tries to set boundaries around what I can do or say, which made for some pretty rebellious teen years. (The clues were there early. I idolized Sarah Jessica Parker in Girls Just Want to Have Fun and thought it was perfectly acceptable to sneak out of your house to enter a dance contest.)

As an adult, I’ve relaxed my rule-breaking ways (and learned I should never, ever enter dance contests), but I have not abandoned my rebelliousness completely. Instead, I’ve turned it inward and started to explore rule breaking via my writing. Creatively, I prefer to explore characters and even writing styles that don’t adhere to the accepted standards. That’s really what makes writing fun.

As an adult, I’ve relaxed my rule-breaking ways (and learned I should never, ever enter dance contests), but I have not abandoned my rebelliousness completely. Instead, I’ve turned it inward and started to explore rule breaking via my writing. Creatively, I prefer to explore characters and even writing styles that don’t adhere to the accepted standards. That’s really what makes writing fun.

But are there rules in writing that should always be followed, no matter what? Even the most lackadaisical grammarian would probably say yes. The constant criticism of the misuse of “your” vs “you’re” on social media tells me many people take their grammar very seriously. And, if you’re a writer, editor or reader, you probably have your own particular grammar pet peeves. (Mine are semicolons and run-on sentences.)

But, why do we cling to these rules? I’ve written on this blog before about “grammandos” – people who are a bit militant about grammar. And why maybe we should all relax and be more flexible with language. Writing and language shouldn’t be so stressful. Sometimes breaking the rules is fun! (Remember, if Sarah Jessica says so, it must be true.)

But are there some rules so sacred you should never, ever break them, right? Maybe not…

Let’s take a look at some “sacred” writing rules, relating to both grammar and style, that might be worth breaking.

Tearing down sacred grammar rules 101

Grammar Rule #1: When writing, you must use complete sentences.

General rules for complete sentences include:

- Begins with a capital letter

- Includes an end mark (e.g., period [.])

- Must contain at least one main clause with an independent subject and verb

- Must express a complete thought

Honestly, complete sentences aren’t all that great. Right? As I’m sure grammandos and most people realize, “Right?” isn’t a complete sentence. It’s a sentence fragment. And I like sentence fragments. When used well, they can be really effective in writing.

Sentence fragments are particularly effective when trying to write in a first person to make it sound more like someone thinks or speaks. Sentence fragments can also set a tone or represent a feeling (e.g., excitement, confusion).

Here’s an example of a paragraph full of sentence fragments from the classic children’s book, A Wrinkle in Time by Madeline L’Engle.

“IT was a brain. A disembodied brain. An oversized brain, just enough larger than normal to be completely revolting and terrifying. A living brain. A brain that pulsed and quivered, that seized and commanded. No wonder the brain was called IT.”

If it’s good enough for a classic children’s author, I don’t see the problem. I think it’s perfectly fine to break this rule as much as you want!

Grammar Rule #2: When writing, you must use correct spelling.

Oh. Spelling. (Like how I did that, NOT complete sentences. It’s fun, right?) This one seems like a no-brainer.

Oh. Spelling. (Like how I did that, NOT complete sentences. It’s fun, right?) This one seems like a no-brainer.

First, let me say that I am the Lois Lane of the spelling world. I suck at it.

As a young child, I spelled the word “wash” like it sounded to me. Back then a few of my words were tinged by a southern accent. Although much of Northern Virginia rebuffs the idea we’re part of the South, being below the Mason-Dixon line means the accent can creep in here and there. And being so close to the US Capitol, we say the word “Washington” a lot.

When I was young, I pronounced it as “Warshington.” Being severely and detrimentally hooked on phonics, I also spelled it the way it sounded with the “r.” At some point, I lost both the accent and figured out the correct spelling, but not before much ridicule for both, thus cementing this memory into my brain forever.

While it would not be good to spell Washington with an r in a newspaper article, in other instances it may not be wrong. For example, misspellings are often useful when trying to convey speech patterns of characters. If I were writing a book from the perspective of a character with a southern accent, you can bet Washington and all its variations (wash, washer, washing machine), would be spelled with an “r.”

In addition, sometimes misspellings can be used for puns or to play on words and ideas. When writing my book, The Travelers, I wrote a line that said something like, “No body would make her feel comfortable.” My editor kept changing it back to “Nobody” (one word.) I’d return it with a comment to keep it as two words and it got a little comical after a while. Finally, I explained that the character literally changes bodies and, therefore, she is not comfortable any physical body. I also wanted the sentence to have the implication that nobody (as in another person) could make her feel comfortable either. So while it had two meanings, the primary meaning was “No” space “body.”

Sometimes it can be fun to play with spelling…it just confounds your poor editors.

Grammar Rule #3: Beginning and ending sentences with conjunctions and prepositions, respectively.

A conjunction, for anyone who hasn’t been back to high school English or seen School House Rock lately, is a like a little connector in a sentence: and, because, but, or, so, also. In school, at least where my daughter attends, children are still taught that sentences should never start with conjunctions. However, many people have come to terms with starting a sentence with “so,” “also” or “but.”

A conjunction, for anyone who hasn’t been back to high school English or seen School House Rock lately, is a like a little connector in a sentence: and, because, but, or, so, also. In school, at least where my daughter attends, children are still taught that sentences should never start with conjunctions. However, many people have come to terms with starting a sentence with “so,” “also” or “but.”

BUT, the use of the words “and,” “because” and “or” still tends to be less acceptable. Perhaps it shouldn’t be. It was good enough for the late, great Johnny Cash. “Because you’re mine, I walk the line.” Why not the rest of us?

“Because you’re mine, I walk the line.”

Ending a sentence with a preposition is also what I’d call an “old school” (i.e., archaic) rule. In doing a bit of research, it seems this rule was never really a rule at all. Yet it has persisted to plague the grammar world!

Apparently, English poet, and it seems general snob, John Dryden invented the “rule” (using a specious Latin analogy) in an attempt to try to make another poet (Ben Jonson) appear inferior. Apparently, the “rule” he concocted was so ridiculous that a linguist by the name Mark Liberman once said, “It’s a shame that Jonson had been dead for 35 years at the time, since he would otherwise have challenged Dryden to a duel, and saved subsequent generations a lot of grief.”

Maybe this is one rule we can not just break, but take off the books forever.

It’s not just grammar, it’s style too!

Not only are there grammar rules, but there are also generally accepted rules of style that define “good writing.” Here are a few style rules I’ve seen that maybe don’t need to be followed THAT strictly.

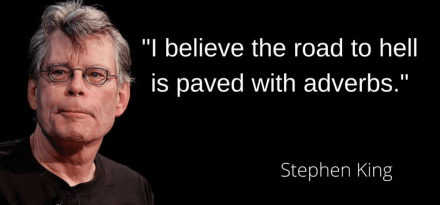

Style Rule #1: No adverbs

This particular piece of advice is most often attributed to Stephen King, who has a famous book on writing, literally called On Writing. For King, apparently, the road to hell is paved with adverbs, which is a pretty drastic concept. I mean good intentions are really pissed right now because they thought they had that market cornered.

This particular piece of advice is most often attributed to Stephen King, who has a famous book on writing, literally called On Writing. For King, apparently, the road to hell is paved with adverbs, which is a pretty drastic concept. I mean good intentions are really pissed right now because they thought they had that market cornered.

Not to argue with a great novelist like King, but I’m inclined to believe adverbs aren’t all bad. Like most things, when used sparingly and effectively, they can have a great impact. (See what I did there…I used adverbs! And I think it works.)

Adverbs also need to suit the style and voice of the book. I’d like someone to tell J. K. Rowling that adverbs are bad. She uses them quite often and King himself even said of her “Rowling has never met an adverb she didn’t like.” Yet her books are really, really, really popular and considered well-written…So, does that mean the road to hell is actually just paved with bad writing advice?

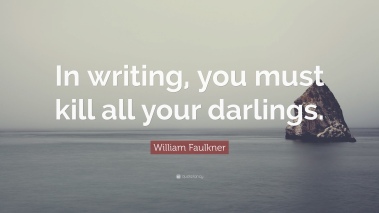

Style Rule #2: Kill your darlings

This can mean lots of things in terms of writing advice. Some take it to mean, literally, kill off your favorite characters. But more often it’s in reference to stepping back and looking at your work objectively and without sentimentality. This can mean reading your work for crutches in your writing, such as phrases you use repeatedly or use of colloquialisms/idioms/clique sayings (eg, “figurative language” such as “time is money”).

This can mean lots of things in terms of writing advice. Some take it to mean, literally, kill off your favorite characters. But more often it’s in reference to stepping back and looking at your work objectively and without sentimentality. This can mean reading your work for crutches in your writing, such as phrases you use repeatedly or use of colloquialisms/idioms/clique sayings (eg, “figurative language” such as “time is money”).

But even this rule is made to be broken. Perhaps those repetitive phrases reflect the character or the situation well and provide continuity to a story. In a book that jumps perspectives across several characters, using the same language specific to a character can be helpful for re-orienting a reader back to that character’s mindset.

And although I generally agree colloquialisms and idioms should be avoided, even figurative language can have a place in writing, particularly in dialogue or when used cleverly to make a point about a person or character. Steinbeck, Shakespeare, Fitzgerald all used idioms, again sparingly and appropriately. But they used them.

As they say, rules are meant to be broken…I think this is at least true in writing (and when sneaking out of the house to participate in a dance contest).

For more on the fun of writing rule breaking, check out this great article called “These Famous Authors Made It Okay To Commit Grammar No-No’s.“

So are you a rule follower when it comes to writing (or what you like in terms of reading) or are you a rule breaker?

June 2, 2018 at 11:52 am

Rules give structure and a common platform. If people like the feeling you generate with your words you’ve created a following and perfectly following the rules of writing isn’t a guarantee of anything. Even the grammar commandos won’t give you a gold star or like your perfect writing – it’ll simply be neat. Great post, great debate all writers wrestle with.

LikeLiked by 1 person

June 2, 2018 at 12:01 pm

Thanks! I think it’s a fun topic to explore. And it’s always interesting to hear people’s thoughts on the subject! Thanks for sharing yours!

LikeLiked by 1 person

June 2, 2018 at 12:05 pm

I love this topic, perfect grammar evades me and I would like to grow but I find honoring rules could keep me paralyzed from writing for life.

LikeLiked by 1 person

June 2, 2018 at 12:07 pm

Perfect grammar evades me too, and I write and edit for a living! No one is perfect. We writers shouldn’t feel so much pressure to be. 🙂 It can feel very paralyzing sometimes. I totally understand that.

LikeLiked by 1 person

June 2, 2018 at 12:09 pm

Stephen King’s book (which you mentioned) actually really helped me to just go for it and make the content I want. He was surprisingly encouraging for a bleak horror writer.

LikeLiked by 1 person

June 3, 2018 at 10:30 am

Ha! Yes good to know you can terrify people with your stories and not with your writing advice!

LikeLiked by 1 person

June 2, 2018 at 1:37 pm

I totally agree. Sometimes I get so bogged down in what is right that I end up writing nothing!

LikeLiked by 1 person

June 3, 2018 at 10:34 am

That’s the worst! I feel that way too sometimes.

LikeLiked by 1 person

June 3, 2018 at 2:23 am

This made me think of one of my favourite writers James Elroy. His style is not your typical way of writing and can take a bit of time to adjust to.

I imagine it’s part of your journey of writing finding what represents you best.

And if people didn’t challenge and evolve and force changes where would we still be in life?

LikeLiked by 1 person

June 3, 2018 at 10:29 am

So true! I haven’t read any James Elroy. I feel like I need to!!

LikeLike

June 3, 2018 at 3:19 pm

Yup, break those rules! Just… make sure you know the rule and are aware you are breaking it. (At least, that’s my theory.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

June 3, 2018 at 3:31 pm

Sounds like a good theory!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

June 5, 2018 at 10:31 pm

When I am trying to get ideas on a page, I tend to not worry about grammar very much. I think it just stops my idea flow. But your post made me realize again just how important it is to keep those rules in mind!

LikeLiked by 1 person

June 6, 2018 at 10:02 am

thanks! 🙂 I’m the same way, grammar be gone when the ideas are flowing! You can fix that later!

LikeLiked by 1 person

June 8, 2018 at 2:26 pm

hehe I really relate to being a rule breaker 😉 That said, grammar’s the one area where I am often a stickler. But with THAT SAID, there are still areas, as you showed, areas where grammar can be manipulated for artistic purposes. Also, yes, there are certain grammar myths (like “you shouldn’t start/end a sentence with a preposition) which serve *zero* purpose and were just made up in the first place. Honestly, I agree with you on the style aspects as well- I have *no qualms* with adverbs. And considering the fact I don’t actually like King’s writing (I know, shock horror), but do like Rowling’s- I’m quite confident to say that’s a matter of taste and not a rule at all. It’s also funny that you included Faulkner’s quote- again, I find it funny that I don’t agree with the rule and realllly am not a Faulkner fan. But even if I get past that, it’s just an opinion and not a rule. I’m not saying it can never work, but I think people can have better reasons to trim their work/kill off a character and could easily lead to unnecessary character deaths and bland writing. Totally agree that rules are made to be broken! Love this post!

LikeLiked by 1 person

June 9, 2018 at 2:56 pm

Thank you! Yeah. I’m not a fan of the kill off characters interpretation of kill your darlings. At this point it’s so expected, it’s more expected NOT to do that!

LikeLiked by 1 person

June 9, 2018 at 9:53 pm

Yeah for sure!

LikeLiked by 1 person